Heart surgery isn’t something most people think about until it’s suddenly necessary. Whether it’s a bypass, valve replacement, or repair of a damaged artery, the decision to operate isn’t made lightly. Doctors don’t just look at your symptoms-they weigh a whole list of hidden risks. Some people walk into surgery with a high chance of recovery. Others face serious, sometimes life-threatening complications. So who’s truly at high risk for heart surgery?

Age isn’t just a number-it’s a major factor

People over 75 have a significantly higher chance of complications after heart surgery. Studies from the American Heart Association show that patients in this age group are nearly three times more likely to need intensive care after surgery than those under 65. It’s not just about being older. As we age, the heart muscle stiffens, blood vessels lose flexibility, and kidneys and lungs don’t recover as quickly. Even if someone feels active and healthy, their body’s ability to handle the stress of open-heart surgery drops sharply after 75.

That doesn’t mean seniors can’t have surgery. Many 80-year-olds recover well. But doctors look harder at their overall health-not just their heart. A 78-year-old with strong lungs, good kidney function, and no diabetes has a much better outlook than a 72-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

Diabetes changes everything

If you have diabetes, especially if it’s poorly controlled, your risk of infection, poor wound healing, and long-term complications after heart surgery jumps dramatically. Blood sugar levels above 180 mg/dL before surgery increase the chance of sternal wound infections by more than 50%. These infections can lead to months of antibiotics, repeat surgeries, and even death.

Diabetes also damages small blood vessels that help deliver oxygen to healing tissues. After bypass surgery, those tiny vessels are critical for keeping the new grafts open. High sugar levels make them more likely to clog or fail. Patients with diabetes are also more likely to develop kidney problems after surgery, which can turn a routine procedure into a life-or-death situation.

Previous heart attacks or heart failure

Having had a heart attack in the past six months is one of the biggest red flags for surgeons. The heart muscle is still healing, and adding surgical stress can trigger another attack or even sudden cardiac arrest. Similarly, if you’re already in heart failure-meaning your heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs-your chances of surviving surgery drop.

Doctors use a score called the ejection fraction (EF) to measure this. An EF below 30% means your heart is pumping less than a third of the blood it should. Patients with EF under 30% have nearly double the risk of dying within 30 days of heart surgery compared to those with EF above 50%. Even if you feel fine, your heart might be barely holding on.

Chronic lung disease makes recovery harder

Many people don’t realize how much heart surgery depends on healthy lungs. After open-heart surgery, you need to breathe deeply and cough to clear fluid. If you have COPD, emphysema, or severe asthma, your lungs can’t handle the strain. This leads to pneumonia, prolonged breathing tube use, and longer ICU stays.

One study of over 12,000 heart surgery patients found that those with moderate to severe lung disease were 4.5 times more likely to need mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours. That’s not just uncomfortable-it increases the risk of brain injury, kidney failure, and death. Surgeons often require lung function tests before approving surgery for patients with a history of smoking or chronic cough.

Obesity and extreme weight

Being overweight adds stress to the heart, but extreme obesity-BMI over 40-is a major surgical risk. Fat tissue doesn’t heal well. Incisions take longer to close, and the risk of infection rises. The deeper the chest fat, the harder it is for surgeons to reach the heart, which can lead to longer procedures and more blood loss.

Obese patients are also more likely to develop blood clots in the legs (deep vein thrombosis) that can travel to the lungs. They’re more likely to have sleep apnea, which makes anesthesia riskier. One hospital tracked over 5,000 patients and found that those with BMI over 40 had a 37% higher chance of needing a second surgery within 30 days due to complications.

Kidney disease is a silent danger

Your kidneys help remove drugs, balance fluids, and control blood pressure-all things that are critical after heart surgery. If your kidneys are already damaged (even mildly), surgery can push them into failure. This is especially true when contrast dye is used during imaging tests before surgery.

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 or worse have a 30% higher risk of dying within a year after heart surgery than those with healthy kidneys. Many don’t realize they have CKD until after surgery. Doctors check creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) before approving any cardiac procedure. If your GFR is below 45, your risk rises sharply.

Smoking and substance use

Smoking doesn’t just hurt your lungs-it weakens your heart’s ability to recover. Nicotine tightens blood vessels, carbon monoxide reduces oxygen in the blood, and tar damages the lining of arteries. Even if you quit a month before surgery, your body still carries the damage.

Patients who smoke within 30 days of surgery are twice as likely to have breathing problems, wound infections, and heart rhythm issues. Alcohol abuse is just as dangerous. Heavy drinkers often have weakened heart muscle, poor nutrition, and liver damage-all of which make anesthesia and recovery riskier. Surgeons often require proof of abstinence for at least 6 weeks before scheduling surgery.

Other conditions that raise the risk

There are several less obvious factors that doctors watch closely:

- Autoimmune diseases like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis can cause inflammation that affects heart tissue and slows healing.

- Cancer, especially if you’re undergoing chemotherapy, weakens your immune system and increases infection risk.

- History of stroke means your brain may not handle the changes in blood flow during surgery.

- Malnutrition or severe weight loss reduces your body’s ability to repair itself after surgery.

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure can cause bleeding during or after the operation.

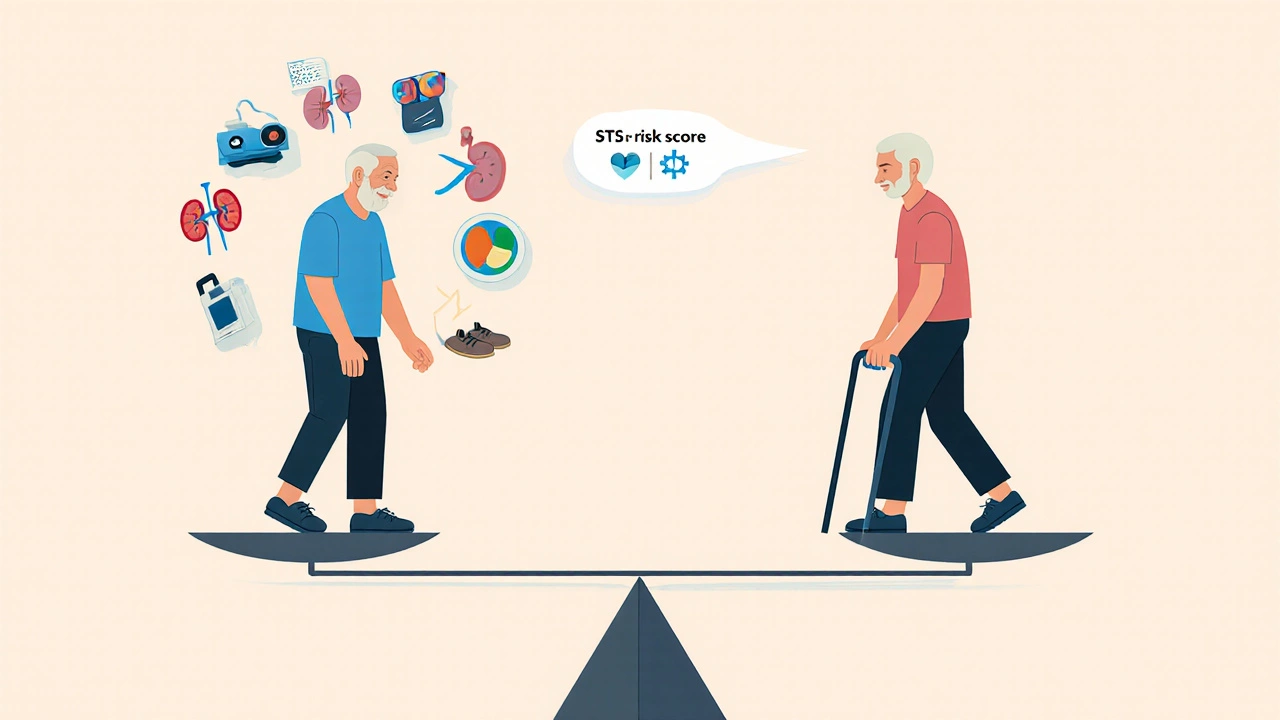

Doctors don’t look at these in isolation. They use a scoring system called the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk calculator. It combines age, diabetes, kidney function, lung health, and other factors into a single percentage that predicts your chance of dying within 30 days of surgery.

What happens if you’re high risk?

If you’re flagged as high risk, surgery isn’t automatically off the table. It just means the team will explore every alternative first. They might try:

- Medications to manage symptoms instead of surgery

- Less invasive procedures like TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) instead of open-heart valve surgery

- Stenting for blocked arteries instead of bypass

- Cardiac rehab to strengthen the heart before surgery

Some patients are referred to specialized centers that handle high-risk cases. These hospitals have teams trained in complex cases, better ICU care, and protocols to reduce complications. They might also use advanced monitoring during surgery or newer techniques like off-pump bypass, which avoids the heart-lung machine.

Can you lower your risk before surgery?

Yes-if you act early. Even a few weeks of preparation can make a big difference:

- Quit smoking at least 6 weeks before surgery-this alone cuts infection risk by nearly half.

- Control blood sugar with diet, medication, and regular checks. Aim for fasting levels under 130 mg/dL.

- Start walking daily-even 20 minutes a day improves lung and heart function.

- Get your nutrition right-protein helps healing. If you’re losing weight, talk to a dietitian.

- Stop alcohol completely for at least 4 weeks before surgery.

- Treat sleep apnea with a CPAP machine if you have it-this reduces anesthesia risks.

These aren’t just suggestions. They’re proven ways to improve your odds. One study showed that patients who followed these steps reduced their complication rate by 41%.

Final thought: Risk isn’t a yes-or-no

There’s no single factor that automatically disqualifies someone from heart surgery. It’s the combination that matters. A 76-year-old with diabetes, kidney disease, and COPD is at much higher risk than a 76-year-old with just one condition. The goal isn’t to avoid surgery at all costs-it’s to make sure the benefits outweigh the dangers.

If you or a loved one is being evaluated for heart surgery, ask your doctor: "What’s my specific risk, and what can we do to lower it?" Don’t accept vague answers. Request your STS risk score. Ask about alternatives. Push for a second opinion if needed. Your life depends on making the right call.

Can someone be too old for heart surgery?

Age alone doesn’t disqualify someone. Many patients over 80 have successful heart surgeries. What matters more is overall health-kidney function, lung capacity, diabetes control, and mobility. Surgeons use risk calculators that weigh multiple factors, not just age. A healthy 82-year-old may be a better candidate than a frail 65-year-old with multiple chronic conditions.

Does diabetes always mean you can’t have heart surgery?

No, but it does increase risk significantly. Poorly controlled diabetes raises infection rates, delays healing, and harms blood vessels needed for bypass grafts. If your blood sugar is managed well-with HbA1c under 7%-and you don’t have kidney damage, surgery is often still possible. Many diabetic patients undergo bypass or valve surgery successfully every year.

What’s the safest type of heart surgery for high-risk patients?

Minimally invasive options are often safer. For valve problems, TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) replaces the valve through a small incision in the leg, avoiding open-chest surgery. For blocked arteries, stenting can be done without stopping the heart. These procedures have lower infection rates, shorter recovery times, and fewer complications in high-risk patients. But they’re not always an option-your anatomy and condition determine what’s possible.

How long should I stop smoking before heart surgery?

At least 6 weeks. Quitting 4 weeks before surgery helps, but 6 to 8 weeks gives your lungs and blood vessels time to begin healing. After 6 weeks, your risk of pneumonia and poor wound healing drops by nearly 50%. Even cutting back isn’t enough-you need to stop completely. Nicotine patches or gum are okay, but avoid vaping or chewing tobacco.

Can weight loss improve my chances of heart surgery?

Yes-even losing 5 to 10 pounds before surgery can reduce complications. Less fat means easier access for surgeons, lower risk of infection, and better breathing. If you’re severely obese, a doctor might recommend a short-term nutrition plan or refer you to a bariatric specialist. The goal isn’t to reach a "perfect" weight-it’s to improve your body’s ability to heal and survive the stress of surgery.