Cancer Survival Calculator

Cancer Survival Calculator

Learn how survival rates differ by cancer type and detection timing. These calculations are based on current medical data from the American Cancer Society and National Cancer Institute.

Why this matters: Early detection can dramatically improve outcomes. For pancreatic cancer, catching it early increases survival from 10% to 47%.

Tip: Symptoms like persistent abdominal pain (pancreatic), memory loss (brain), or unexplained weight loss (ovarian) should be checked promptly.

When someone hears the word cancer, their mind jumps to fear. But not all cancers are the same. Some respond well to treatment. Others fight back with brutal efficiency. If you’re asking what cancer is hardest to survive, the answer isn’t just one disease-it’s a group of cancers that slip through detection, resist treatment, and spread before most people even feel symptoms.

Pancreatic Cancer: The Silent Killer

Pancreatic cancer doesn’t shout. It whispers. By the time symptoms like jaundice, weight loss, or abdominal pain show up, the cancer has often spread beyond the pancreas. Only about 10% of people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer survive five years. That’s the lowest survival rate of any major cancer.

Why? The pancreas sits deep inside the body, hidden behind the stomach and intestines. There’s no routine screening test like a mammogram or colonoscopy. By the time it’s found, it’s usually stage III or IV. Even when surgeons remove the tumor, recurrence is common. Chemotherapy helps, but rarely cures. The median survival for advanced cases is less than a year.

Doctors call it a "silent killer" for a reason. A 2023 study from the American Cancer Society showed that nearly 80% of pancreatic cancers are diagnosed after they’ve already spread. That’s why survival hasn’t improved much in the last 30 years.

Glioblastoma: The Brain’s Most Aggressive Enemy

If pancreatic cancer is silent, glioblastoma is a storm inside the skull. This aggressive brain tumor grows fast, spreads through brain tissue like roots through soil, and resists every treatment thrown at it. The average survival after diagnosis is just 12 to 18 months. Only 5% of patients live five years or longer.

What makes it so hard to treat? The blood-brain barrier blocks most chemotherapy drugs from reaching the tumor. Surgeons can’t remove every cancer cell without damaging vital brain functions. Radiation helps, but the tumor always comes back-often in a more resistant form. Even the newest immunotherapies, which work wonders for melanoma or lung cancer, barely make a dent here.

Patients often lose speech, movement, or memory before the end. There’s no early warning. A headache, a memory lapse, or a sudden seizure might be the first sign. By then, it’s usually too late.

Lung Cancer: Still the Top Cause of Cancer Deaths

Lung cancer kills more people every year than breast, colon, and prostate cancer combined. While survival has improved for some subtypes-especially non-small cell lung cancer with targeted therapies-overall, the five-year survival rate is still only 22%.

Why? Because most cases are found late. Smokers and former smokers are at highest risk, but 20% of lung cancer patients have never smoked. Early-stage lung cancer rarely causes symptoms. By the time coughing, chest pain, or shortness of breath appear, the cancer has often spread to lymph nodes or other organs.

Low-dose CT scans for high-risk individuals have helped catch some cases early. But access is limited, especially outside major cities. Even when caught early, recurrence rates remain high. New drugs like osimertinib and pembrolizumab have given hope, but they’re not cures. For many, it’s still a race against time.

Esophageal Cancer: A Slow Burn With a Deadly End

Esophageal cancer grows in the tube that connects your throat to your stomach. It’s rare compared to other cancers, but deadly. The five-year survival rate is just 20%. If it’s caught early, survival jumps to 47%. But early detection is rare.

Barrett’s esophagus-a condition caused by chronic acid reflux-is a known risk factor. But most people with reflux never get screened. Symptoms like trouble swallowing or chest pain often get dismissed as heartburn or indigestion. By the time patients see a doctor, the cancer has invaded deeper layers of the esophagus or spread to nearby organs.

Surgery is the main treatment, but it’s complex and carries high risks. Chemotherapy and radiation help, but responses are inconsistent. The location makes it hard to treat without damaging swallowing function. Many patients lose weight rapidly and struggle to eat, which weakens them further.

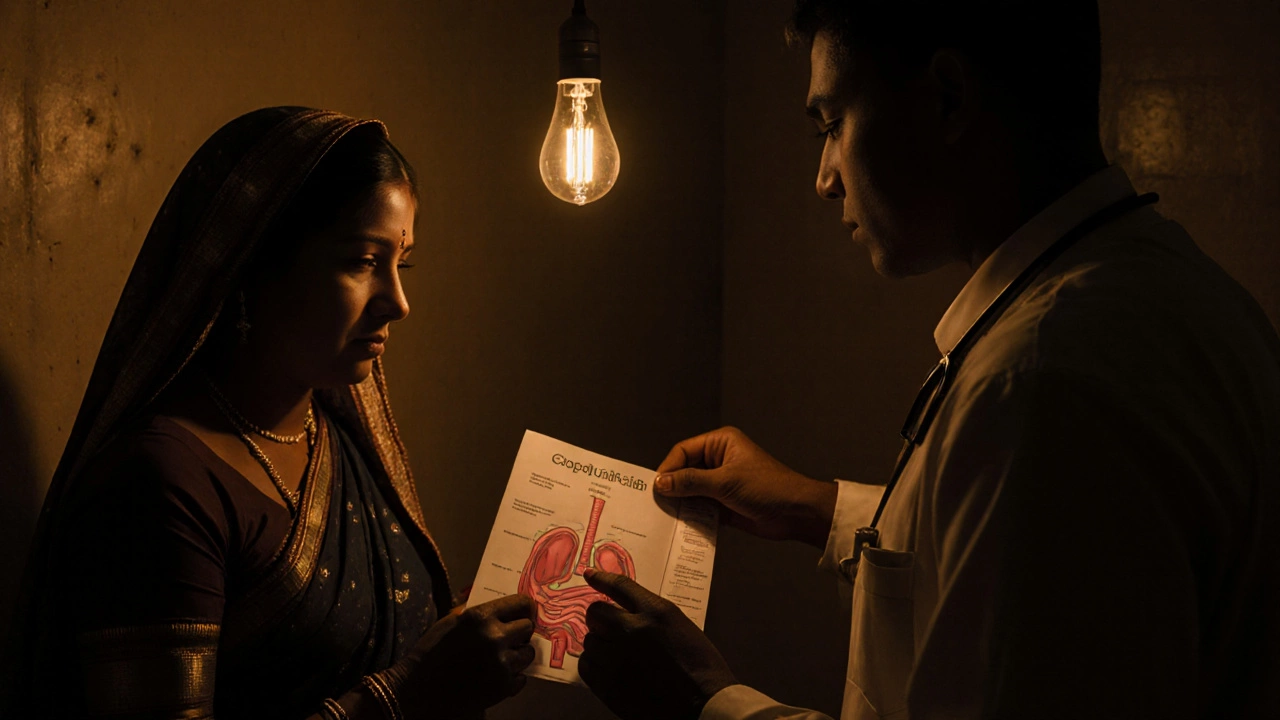

Ovarian Cancer: The Whisper That Turns to a Scream

Ovarian cancer is called the "silent killer" too, but for different reasons. Early symptoms-bloating, feeling full quickly, pelvic pain-are so common they’re often ignored. By the time doctors find it, 70% of cases are already stage III or IV.

The five-year survival rate for advanced ovarian cancer is around 30%. For early-stage, it’s 90%. But catching it early is the problem. There’s no reliable screening test. CA-125 blood tests and ultrasounds aren’t accurate enough for routine use. BRCA gene mutations raise risk, but not everyone gets tested.

Treatment involves surgery and chemo, but the cancer often returns. New drugs like PARP inhibitors have extended survival for some, especially those with BRCA mutations. But for the majority, it’s a cycle of remission and recurrence.

Why Do These Cancers Survive Against Treatment?

These cancers share three deadly traits:

- No early detection: No simple, accurate test exists to catch them before they spread.

- Aggressive biology: They grow fast, invade nearby tissues, and spread early-even when small.

- Resistance to treatment: They adapt quickly to chemotherapy, radiation, and even newer targeted therapies.

Unlike breast or prostate cancer, where early screening saves lives, these cancers are like thieves who break in while you’re asleep. By the time you wake up, they’ve already taken what they came for.

What’s Changing? Hope on the Horizon

It’s not all doom. Research is moving faster than ever.

For pancreatic cancer, scientists are testing blood tests that detect tumor DNA before symptoms appear. Early trials show promise. Immunotherapy combinations are being tested in clinical trials. Some patients with rare genetic mutations are responding to personalized treatments.

Glioblastoma researchers are using AI to map tumor growth patterns and design custom radiation plans. Tumor-treating fields (TTFields), a low-intensity electric therapy, have extended survival in some patients.

Lung cancer has seen the biggest gains. Liquid biopsies now detect mutations from a simple blood draw. Targeted drugs for EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and other mutations have turned some stage IV cases into chronic conditions.

But these advances are still limited. They help a fraction of patients. And they’re expensive. Access isn’t equal. In places like rural India or small towns in the U.S., these tools are out of reach.

What Can You Do?

Survival isn’t just about the cancer you get. It’s about when you find it-and how you’re treated.

- If you smoke, quit. Lung cancer risk drops by half after 10 years.

- If you have chronic acid reflux, get checked for Barrett’s esophagus.

- If you have a family history of ovarian, pancreatic, or breast cancer, ask about genetic testing.

- Don’t ignore persistent bloating, unexplained weight loss, or new neurological symptoms.

- Know your body. If something feels off for more than two weeks, see a doctor.

Early detection saves lives. But for the hardest cancers, it’s not just about screening. It’s about awareness. It’s about not dismissing symptoms. It’s about pushing for answers when you feel something’s wrong.

Survival Isn’t Just a Number

Survival rates are statistics. They don’t tell the story of the person fighting. Some people beat the odds. Some live years beyond their prognosis. Others don’t. But every story matters.

The hardest cancers to survive aren’t just about biology. They’re about timing, access, and awareness. Until we can catch them early-or stop them before they start-we’re still playing catch-up.

But the fight isn’t over. Science is getting smarter. Patients are demanding better. And maybe, just maybe, the next breakthrough will come from someone who refused to accept "it’s just the way it is."

What is the most aggressive cancer?

Glioblastoma is considered the most aggressive cancer because it grows rapidly in the brain, spreads through healthy tissue, and resists all standard treatments. Median survival is under 18 months, and recurrence is nearly guaranteed.

Which cancer has the lowest survival rate?

Pancreatic cancer has the lowest five-year survival rate of any major cancer-around 10%. This is due to late detection, lack of screening tools, and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation.

Can you survive stage 4 cancer?

Yes, but survival varies widely by type. For stage 4 pancreatic cancer, survival is typically under a year. For some types of stage 4 lung or breast cancer with targeted therapies, people live five years or longer. It depends on the cancer type, genetics, and treatment options available.

Is there a blood test for pancreatic cancer?

No reliable routine blood test exists yet. CA-19-9 is sometimes used to monitor treatment response, but it’s not accurate for early detection. New tests detecting tumor DNA in blood are in clinical trials and show promise, but they’re not available to the public.

Why don’t we have a screening test for ovarian cancer?

Current tools like CA-125 blood tests and ultrasounds have too many false positives and false negatives. They can’t reliably distinguish early ovarian cancer from benign conditions. Screening healthy women leads to unnecessary surgeries and doesn’t improve survival. Research is ongoing for better biomarkers.

For those facing these cancers, every day counts-not just in treatment, but in asking questions, seeking second opinions, and refusing to give up. The hardest cancers to survive aren’t just diseases. They’re challenges to the entire medical system. And change starts with awareness.