When couples wonder whether In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a assisted reproductive technology that combines egg and sperm outside the body to create an embryo, one frequent question is about the baby's looks. Do IVF babies look like both moms, or does the dad dominate the facial features? The short answer is: genetics, not the IVF process, decides resemblance. Below we break down how genes travel from parents (and possibly donors) to an IVF baby, what traits you can expect, and how to interpret the many myths that float around.

How Genes Shape a Baby’s Face

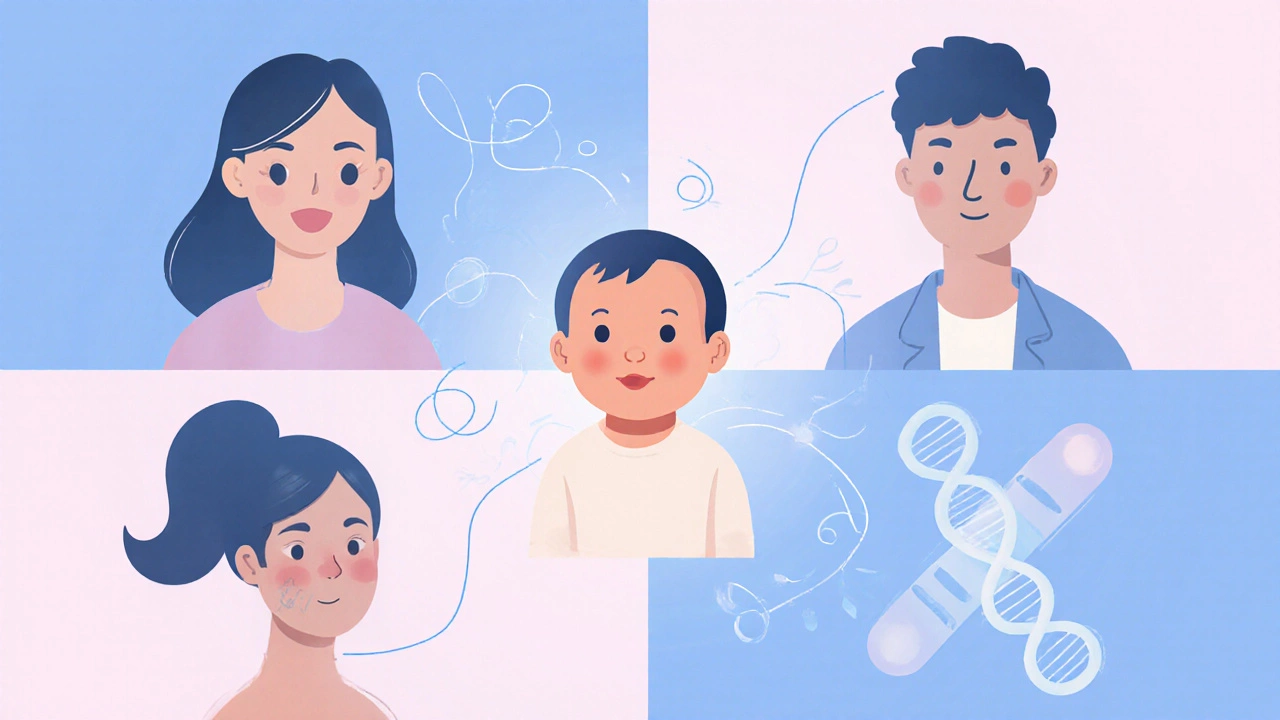

Every person carries two copies of each chromosome - one from each biological parent. Those chromosomes hold the DNA that codes for eye color, hair texture, cheekbones, and countless other features. The combination of the two sets creates the phenotype, the observable traits you see in a newborn.

In a typical pregnancy, the mother provides the egg’s mitochondria (the cell’s power plants) and half the nuclear DNA, while the father provides the other half of the nuclear DNA via sperm. The mitochondria, which carry mitochondrial DNA, are passed almost exclusively from mother to child and have minimal impact on facial appearance. The real visual traits come from the autosomal DNA - the 22 pairs of chromosomes that are not sex‑determining.

IVF Doesn’t Rewrite Your DNA

IVF simply creates the embryo in a lab dish before placing it in the uterus. The lab step does not alter the DNA sequence. Whether you use fresh or frozen eggs, or an embryo created on day 3 versus day 5, the genetic material stays the same. So the baby’s resemblance to its parents is governed by the same rules as any natural conception.

That said, IVF often involves additional variables: donor eggs, donor sperm, or even a gestational carrier (a woman who carries an embryo that isn’t genetically hers). Each of these scenarios introduces new genetic contributors, which can affect how many features look like each mother.

When Both Moms Contribute Genes

In most IVF cycles, a single mother’s egg is fertilized with a partner’s sperm. In that case, the baby will inherit roughly 50% of its nuclear DNA from the mother, 50% from the father. The baby will therefore share many facial traits with the mother, but also display a mix of the father’s features.

If a lesbian couple uses a donor sperm, the biological mother (the egg donor) still provides half the DNA, while the donor sperm supplies the other half. The non‑biological mother may notice some similarity because she shares the pregnancy environment, but genetics won’t make the baby look like her.

When a couple uses a donor egg, the egg donor (often a different woman) supplies half the DNA. In that scenario, the baby may look less like the intended mother and more like the donor egg’s donor. Some parents report striking resemblances to the egg donor’s family even though they never met them.

Traits From Two Moms: Real‑World Examples

- Eye color: Determined by several genes. If both mothers carry a blue‑eye allele, the baby has a higher chance of blue eyes, even if the biological father’s genes favor brown.

- Hair texture: Often a blend. A child born from a mother with curly hair and a donor with straight hair may end up with wavy hair, a middle ground of the two.

- Facial structure: Influenced by dozens of tiny genetic effects. It’s common for an IVF baby to inherit a prominent cheekbone from the egg donor and a softer jawline from the intended mother.

These anecdotes illustrate that resemblance is a mosaic, not a simple “half‑and‑half” split.

Epigenetics - The Environment’s Whisper

Beyond DNA, epigenetics can tweak how genes are expressed. The IVF lab environment, culture media, and even the hormonal regimen used to prepare the uterus may leave tiny marks on the embryo’s DNA. Current research suggests these marks are subtle and usually fade over time, but they can influence early growth patterns.

For example, a study from 2023 in the Journal of Reproductive Medicine found that IVF‑conceived infants had a slightly higher likelihood of being born with a lower birth weight, a factor that can affect facial fat distribution temporarily. However, by age 2, most children’s appearance aligns closely with their genetic blueprint.

Checklist: What Parents Should Know About IVF Baby Resemblance

- Identify the source of each gamete (egg, sperm, or both). This tells you whose DNA is in the baby.

- Remember that mitochondrial DNA comes only from the egg donor and does not influence facial features.

- Consider that donor eggs introduce an entirely new set of facial traits.

- Understand that epigenetic factors are minor and usually fade as the child grows.

- Know that the pregnancy environment can affect weight and skin tone, but not the core genetic resemblance.

- Talk openly with your partner or donor about expectations; many families are surprised by unexpected resemblances.

Keeping these points in mind can help you set realistic expectations and celebrate the unique blend that makes your child special.

Common Myths About IVF Baby Looks

Myth 1: IVF babies always look like the mother because the embryo grows inside her.

Reality: The womb provides nutrients, but the DNA that determines looks comes from the egg and sperm, not the uterus.

Myth 2: All IVF babies resemble the donor more than the intended parent.

Reality: Studies of over 2,000 donor‑egg cycles show that children often resemble the intended mother’s family as much as the donor’s family, especially in traits like eye color and temperament.

Myth 3: IVF changes the DNA sequence, leading to “designer babies”.

Reality: IVF does not edit genes. Gene editing would require technologies such as CRISPR, which are not part of standard IVF protocols.

Comparing Trait Inheritance: IVF vs. Natural Conception

| Trait | IVF (Standard Egg + Sperm) | IVF (Donor Egg or Sperm) | Natural Conception |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Nuclear DNA | 50% mother, 50% father | 50% donor, 50% partner | 50% mother, 50% father |

| Influence of Mitochondrial DNA | From mother’s egg only | From donor egg | From mother’s egg |

| Likelihood of Resemblance to Intended Mother | High (≈50% of facial traits) | Variable - depends on donor’s traits | High (≈50% of facial traits) |

| Epigenetic Impact of Lab Culture | Minor, mostly temporary | Same as standard IVF | None |

Notice that the core genetics stay the same across all three scenarios. The only real difference appears when a donor gamete is used - the donor’s DNA replaces one parent’s contribution.

Practical Steps for Expecting Parents

- Get a clear genetics report. Fertility clinics often provide a brief summary of the donor’s physical traits (eye color, hair type, height). Use it to set expectations.

- Take photos of both biological contributors. Comparing baby photos later becomes easier when you have a reference of the egg donor or sperm donor.

- Observe early milestones. Sometimes a child’s facial features sharpen after the first year as baby fat recedes.

- Celebrate the blend. Even if the baby looks more like one parent, the personality and love come from both families.

By following these steps, you’ll feel more prepared for the surprise moments when your newborn starts to look like someone you know.

Bottom Line on IVF Baby Appearance

The most important takeaway is that IVF babies appearance follows the same genetic rules as any other baby. The IVF process itself doesn’t add a “look‑like‑both‑moms” bonus. What matters is whose DNA is in the mix - the egg, the sperm, and any donors involved. Understanding that map helps you enjoy the journey without getting tangled in myths.

Do IVF babies look more like the mother than the father?

Yes, they usually share about 50% of facial traits with the mother because the mother provides the egg’s DNA and the environment during pregnancy. However, the father’s DNA also contributes equally, so the final look is a blend of both.

If a donor egg is used, will the baby look like the intended mother?

The baby will inherit half of its DNA from the donor egg, so many physical traits may resemble the donor’s family. The intended mother’s contribution comes from the uterus environment, which can affect weight and skin tone but not core facial features.

Can IVF change a baby’s genetic makeup in any way?

No. IVF simply fertilizes the egg outside the body; it does not edit or alter the DNA sequence. Any changes in appearance come from the genetic material supplied by the gametes, not from the lab process.

Do mitochondrial DNA differences affect a baby’s looks?

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the egg and mostly controls cellular energy, not outward appearance. It has virtually no impact on eye color, hair type, or facial structure.

What role does epigenetics play in IVF babies?

Epigenetic marks can influence how genes are turned on or off, but the effect on appearance is subtle and usually temporary. Most studies show that by early childhood, the baby’s look aligns with the underlying DNA.