Pancreatic Cancer Survival Rate Calculator

This tool provides population-level estimates based on medical data, NOT individual prognosis. Survival rates vary significantly based on multiple factors not captured here.

Important Note: The data shown is based on national averages. Actual survival depends on individual treatment response, tumor biology, and access to care.

Your Estimated Survival Rate

13%

Overall 5-year survival rate3.1%

Based on your factorsKey Factors That Impact Survival

Early detection: Only 20% of patients diagnosed early enough for surgery

Stage at diagnosis: Metastatic cases have 3% 5-year survival vs 40% for localized cases

Smoking: Doubles risk of developing pancreatic cancer

Genetic factors: Strong family history increases risk significantly

What You Can Do

If you have risk factors like new-onset diabetes, unexplained weight loss, or persistent abdominal pain, consult your doctor immediately. Early detection can significantly improve outcomes.

Learn about pancreatic cancer symptomsWhen people ask which cancer has the lowest survival rate, they’re not just looking for a name-they want to understand why it’s so deadly, what makes it different, and whether there’s any real hope. The answer isn’t just a statistic. It’s a story of late detection, biological aggression, and limited treatment options. That cancer is pancreatic cancer.

Why pancreatic cancer stands out

Pancreatic cancer doesn’t shout. It doesn’t cause obvious symptoms until it’s spread. By the time someone feels persistent belly pain, loses weight without trying, or notices yellowing skin, the cancer has often moved beyond the pancreas. Over 80% of cases are diagnosed at a late stage, when surgery is no longer an option.

The five-year survival rate for all stages combined is just 13%. That’s lower than lung, liver, or ovarian cancer. For those diagnosed after the cancer has spread to distant organs-about 53% of cases-the survival rate drops to 3%. Compare that to breast cancer, where the five-year survival rate is over 90%, and the difference is stark.

It’s not that pancreatic cancer is rare. About 65,000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the U.S. alone. But its lethality comes from how fast it grows and how well it hides. The pancreas sits deep in the abdomen, behind the stomach. Tumors there don’t press on nerves or organs early on. No cough. No lump. No visible change. Just silent, slow destruction.

What makes pancreatic cancer so hard to treat

Most cancers respond to chemotherapy or immunotherapy to some degree. Pancreatic cancer doesn’t. Its tumors are wrapped in dense, fibrous tissue-like a fortress made of scar tissue. This barrier blocks drugs from reaching the cancer cells. Even when chemo works at first, resistance builds fast.

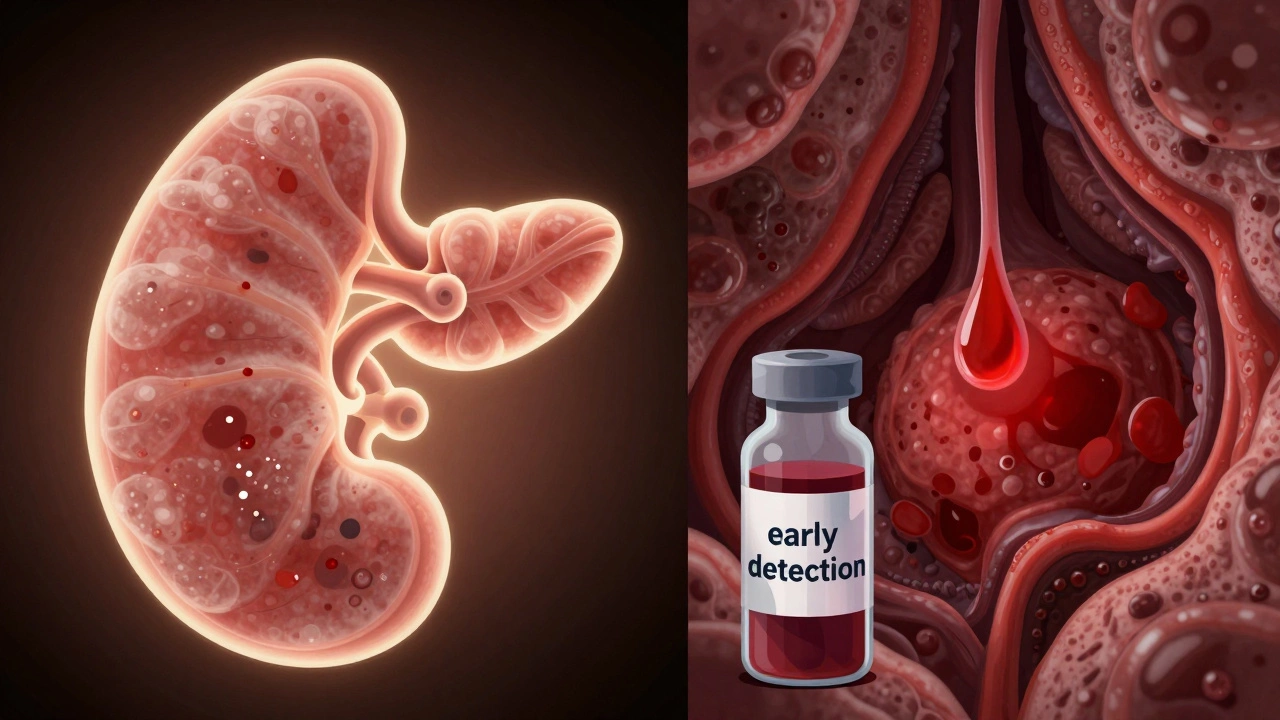

Unlike melanoma or lung cancer, where targeted therapies or immunotherapies have dramatically improved outcomes, pancreatic cancer has seen almost no breakthroughs in the last 20 years. There are no widely available genetic tests that predict who will respond to treatment. And there’s no screening tool-no blood test or scan-for early detection in average-risk people.

Even surgery, the only potential cure, is risky. Only about 20% of patients are candidates. The Whipple procedure, the most common operation, is complex. It removes part of the pancreas, the gallbladder, part of the stomach, and the small intestine. Recovery takes months. And even after a successful surgery, over half the patients see the cancer return within two years.

Who’s at highest risk

Some people are more likely to get pancreatic cancer. Age is the biggest factor. Most cases happen after 65. Smoking doubles the risk. Long-term diabetes, especially if diagnosed after age 50, is a red flag. Chronic pancreatitis-long-lasting inflammation of the pancreas-also increases risk.

Family history matters. If you have two or more close relatives with pancreatic cancer, your risk goes up. Certain inherited gene mutations, like BRCA1, BRCA2, or Lynch syndrome, are linked to higher rates. People of Ashkenazi Jewish descent have a slightly higher chance due to these mutations.

Obesity and heavy alcohol use also play roles. But here’s the catch: many people who get pancreatic cancer have none of these risk factors. That’s what makes it so unpredictable.

What’s changing-slowly

There’s no magic bullet yet, but things are shifting. Researchers are now focusing on early detection in high-risk groups. Blood tests that look for tumor DNA or specific proteins are being tested in clinical trials. One study in the UK found a blood test could spot pancreatic cancer up to three years before symptoms appeared in people with new-onset diabetes.

Some hospitals are starting to screen people with strong family histories using MRI or endoscopic ultrasound. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than waiting for pain to start.

New drug combinations are being tested. One recent trial showed that a regimen called FOLFIRINOX improved survival for some patients by several months. Another, called Gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel, became a standard for advanced cases because it worked better than older drugs.

And then there’s immunotherapy. It rarely works for pancreatic cancer-but for the small group with mismatch repair deficiency (about 1-2% of cases), it can be life-changing. Genetic testing is now recommended for all pancreatic cancer patients, not just those with family history.

What you can do

If you’re healthy and have no family history, there’s no routine screening. But if you’re over 50 and notice unexplained weight loss, new-onset diabetes, or persistent upper abdominal pain that radiates to your back, don’t ignore it. Tell your doctor. Ask for an ultrasound or CT scan. Early detection saves lives-even in pancreatic cancer.

If you have a strong family history or a known genetic mutation, talk to a genetic counselor. They can help you decide if screening with MRI or endoscopic ultrasound makes sense for you. It’s not a guarantee, but it’s a chance.

Stop smoking. Maintain a healthy weight. Limit alcohol. These aren’t just general health tips-they’re direct ways to lower your risk of this deadly cancer.

Hope isn’t gone

Survival rates haven’t budged much in decades, but that’s changing. More research funding is going into pancreatic cancer now than ever before. Labs are testing new drugs, new delivery systems, and even personalized vaccines made from a patient’s own tumor cells.

One patient in Boston, diagnosed at stage 3, responded to a combination of chemotherapy and a custom vaccine. After two years, she was cancer-free. She’s not a miracle. She’s part of a growing group of patients who are beating the odds because science is finally catching up.

Pancreatic cancer is still the deadliest common cancer. But it’s no longer a death sentence for everyone. Knowledge, early action, and access to the right care can make a difference. The goal isn’t just to survive longer-it’s to catch it before it spreads. And that’s where the real fight is.